Recently, the IU East Campus Library gained access to a marvelous set of historical databases covering cultures from all over the world. The Adam Mathew databases, powered by university collections and state institutions such as the British Library, cover historical documents from Central and South America, Asia and Africa. From missionary bulletins printed in Hong Kong to detailed reports from the East India Company, lots of surprises dwell within these amazing resources.

Today, we’ll focus on China. The China: Trade Politics and Culture database spans 1793-1980 and covers everything from biographies and sales records to Chinese Christmas cards. The church bulletins are fascinating mostly for their diary-like entries on life in China in the 19th century and book reviews about Chinese translations. The database provides a helpful chronology, color coded with major topics like government, trade and religion.

Undated Christmas card

But perhaps most interesting is the database’s focus on opium. For centuries used for pain relief and gastrointestinal distress in India and other South Asian nations, opium is not native to China but was used sparingly in medicinal preparations. Other substances such as tea, herbs and cinnabar (an ore of mercury, also used frequently in Western medicine) were much more prevalent in Chinese pharmacopeia. By the late 18th century, however, opium was being smuggled into China in vast quantities, mostly by the British in an effort to open the country to foreign imports without considering the unique structure of Chinese government or developing products the Chinese might find valuable. China’s response to Great Britain’s actions was to place increasingly harsh punishments on those involved in the opium trade, with few results. In 1839, war broke out between China and Great Britain, with the British claiming victory in 1842. The First Opium War, as it was later dubbed, resulted in five ports open to trade between China and many European nations as well as the United States. Hong Kong, the most famous of these ports, was not returned to Chinese rule until 1997, where it is currently governed as an autonomous region. Opium shaped the history of China for over a century, and this database places a strong focus on original documents (mostly from a British perspective) detailing both Opium Wars and the efforts of the Chinese government to combat both addiction and internal dissent.

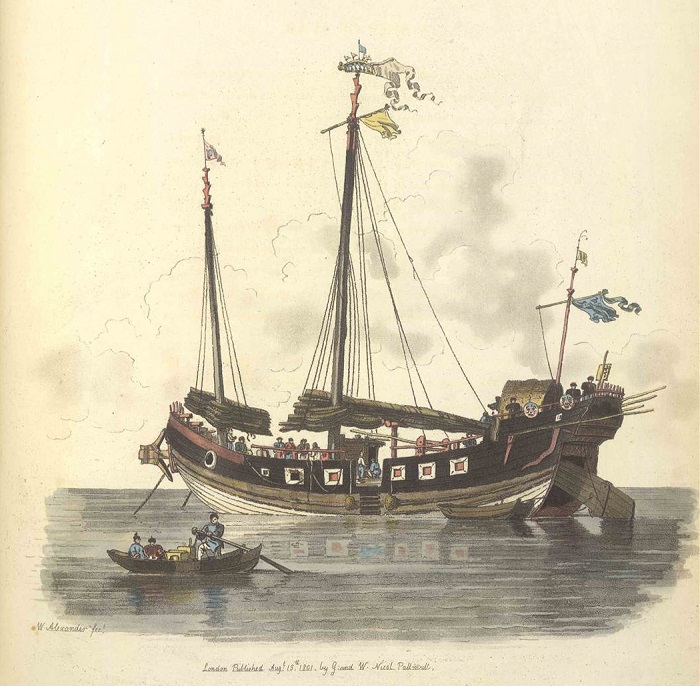

Chinese warship, as drawn by a British illustrator ca. 1801

Beyond the China trade database, we have other resources on Chinese history and culture, particularly its relationship to the West. The China: Culture and Society database, which includes roughly 1200 documents in English from Cornell University, focuses on how the West learned about China and responded to Chinese immigration. Included in the database are documents calling for equal rights for Chinese immigrants, a catalog of Chinese paintings spanning over five centuries and a travel monologue from two Americans detailing a trip from Constantinople (Turkey, now known as Istanbul) and Peking (now Beijing).

Chao Chun Mu, “Think Thrice, then Act”, Yuan Dynasty.

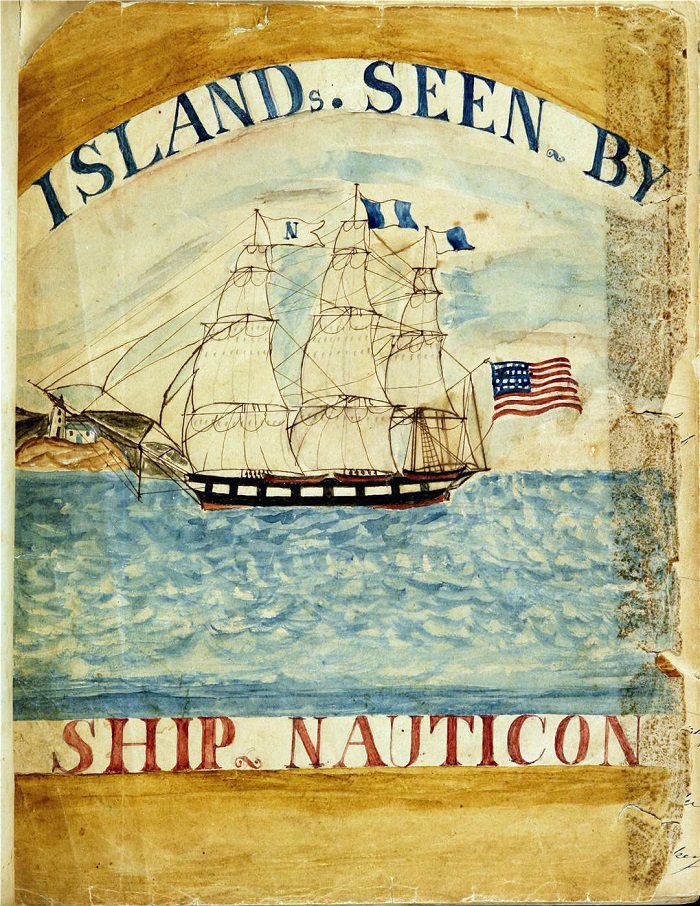

Another database, China, America and the Pacific, includes gorgeous maps in both black-and-white and color, a history of Hawaiian trade and its importance to trade between Asia and the United States, and a journal kept by Susan C. Austin Veeder, the wife of a ship’s captain, who chronicled her travels in one exceedingly rare handwritten, illustrated document.

Hand drawn introductory page to Susan C. Austin Veeder’s journal.

These three Adam Mathew databases provide a unique firsthand look at 18th and 19th century China from a multitude of perspectives. As a source of primary documents they are invaluable in understanding how outsiders understood China and, in some cases, how Chinese people understood themselves. Want to learn more about China’s history and culture? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu.