Every day, new collections of historical treasures are transformed from print or microform versions to digital formats, thanks to technology and the expertise of library staff. They become shared treasures available publicly via online library and museum collections. The New York Public Library Digital Collections has recently added images of African American women who were featured in the 1893 book by Josephine Turpin Washington, Women of distinction: remarkable in works and invincible in character. This collection includes 43 women of exceptional accomplishments. We share ten of them here, and invite you to explore more. Images are all from the NYPL digital collection; additional information about each woman was gathered from the source linked to her name. Interested in exploring other digital collections? IU East Campus Library is here for you! Let us know your interests and we can help you locate historical images online. Just ask! iueref@iue.edu

A popular singer and performer in post-Civil War America, Batson’s marriage to her stage manager, John G. Bergen, in 1887 was one of the first interracial marriages. As her career continued to improve, she toured internationally and met such figureheads as Pope Leo XIII and the Queen of Hawaii. Flora Batson Bergen retired to a life of singing for charities and other philanthropic ventures.

Historians agree that Rosa Dixon was most likely born into slavery, and after the Civil War her family moved to Richmond, Virginia. She worked as the first African American teacher in the Virginia public schools. Her husband, James Bowser, was also a schoolteacher. During her career, Bowser worked to create professional development opportunities for teachers, and was instrumental in the creation of the Virginia Teacher’s Reading Circle in 1887. She was an influential advocate and educator, promoting improved conditions for African Americans mothers. In 1895, Bowser founded the Richmond Woman’s League, an organization that raised money for the legal bills of wrongfully incarcerated African Americans.

Brown was the daughter of two former slaves and worked in the public school system in the early part of her adulthood. She was on the faculty of several colleges, including serving as the Dean of Women at the Tuskegee Institute during 1892-93. An advocate for women’s suffrage, Brown helped to create the Colored Women’s League in Washington D.C. and she served on women’s suffrage committees in her home state of Ohio.

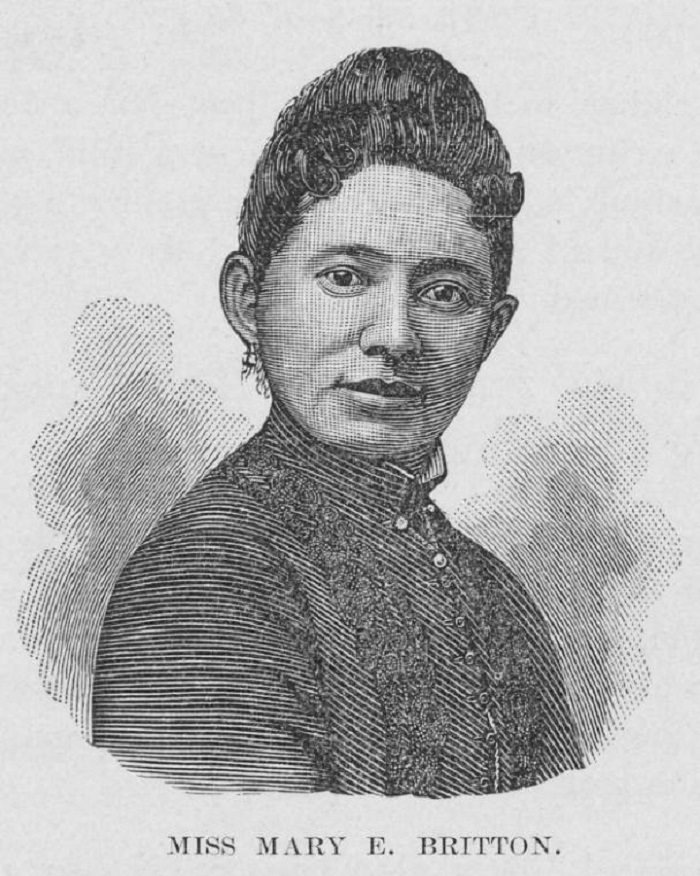

Britton was born in Lexington, Kentucky to a free African American family. Her father was a carpenter and her mother was the biracial daughter of a public official. Her parents were well educated, and Mary and her siblings received the best education available to an African American family. Britton earned a teaching degree, then went on to earn a medical degree from the American Missionary College in Chicago. An advocate for hydrotherapy and electrotherapy, Britton became the first African American woman in Lexington, Kentucky to work as a doctor. In 1892, Britton founded the Colored Orphan Industrial Home, which helped orphans and the elderly.

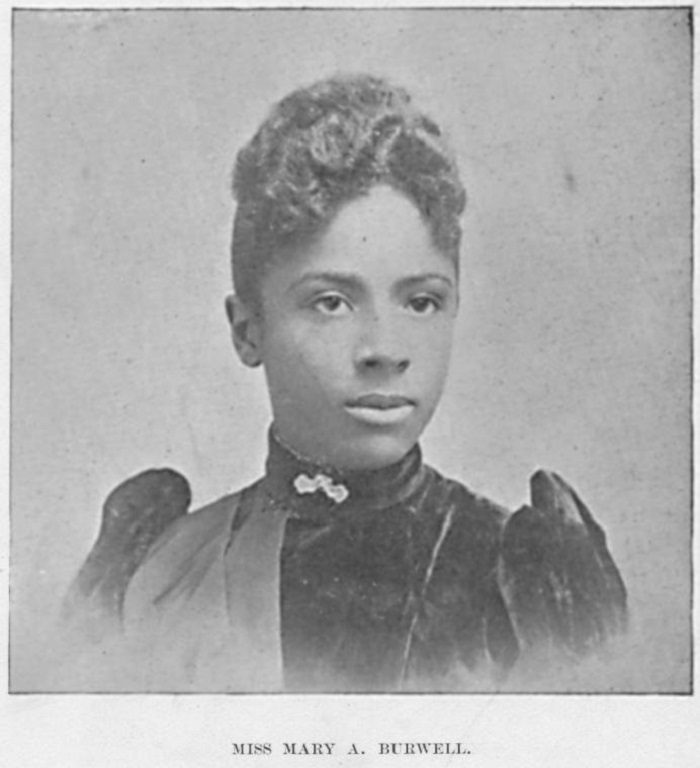

Born into slavery in Virginia, Burwell later moved to Raleigh, North Carolina with an uncle, where she attended school. Burwell worked in the public schools and then at an orphanage in North Carolina. She worked with the orphans to provide performances for potential donors throughout the state. Burwell and her students raised the funds to build better lodgings to accommodate and care for more children.

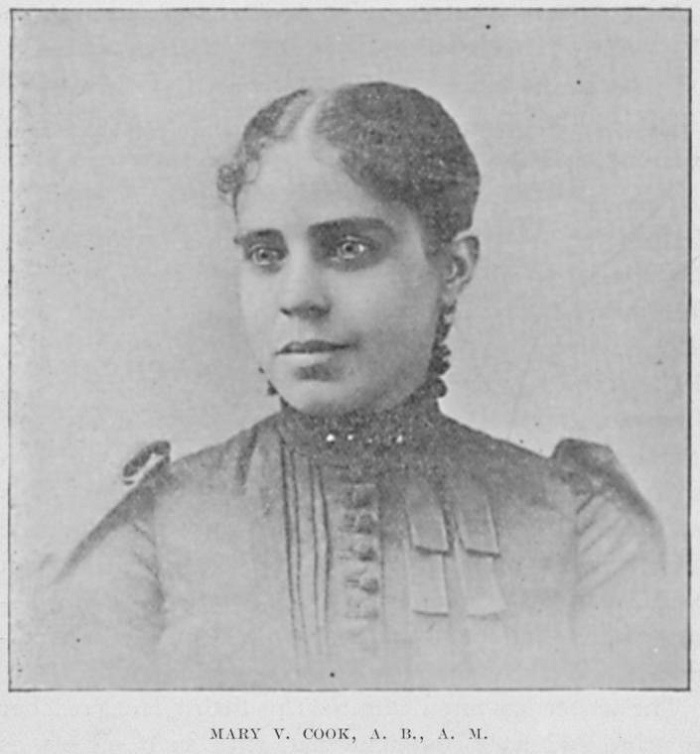

Mary Virginia Cook-Parrish grew up in Kentucky and found it quite difficult to access quality education. Despite that challenge, she became an important leader of her time. Cook-Parrish was a professor at the Kentucky Baptist College. In 1886, she became a journalist reporting on social and educational issues. An accomplished speaker, she gave speeches advocating for women’s equality and social reform. One of Cook-Parrish’s famous speeches was “Female Education” presented to the American Baptist Home Mission Society in 1888.

Historians are unsure of Julia Ringwood’s date of birth or death. However, it is known that she took great interest in the progression of African American influence in popular culture during the time she was alive, in the late 1800s. After marrying Yale student William Coston in 1890, the couple moved to Cleveland, Ohio. While her husband worked as a pastor, Julia Ringwood Coston began Ringwood’s Afro-American Journal of Fashion in order to make up for the lack of an African American presence in fashion journals catering to white women. In order to draw attention to the mistreatment of African American women living in the South, Ringwood included press editorials in her publications, along with fashion advice, articles on homemaking, and etiquette. For a subscription fee of $1.25, subscribers would receive a year of the 12-page journal. The journal was popular throughout the U.S., among both African American and White readers. Ringwood employed and strongly advocated for female writers to contribute to her journal.

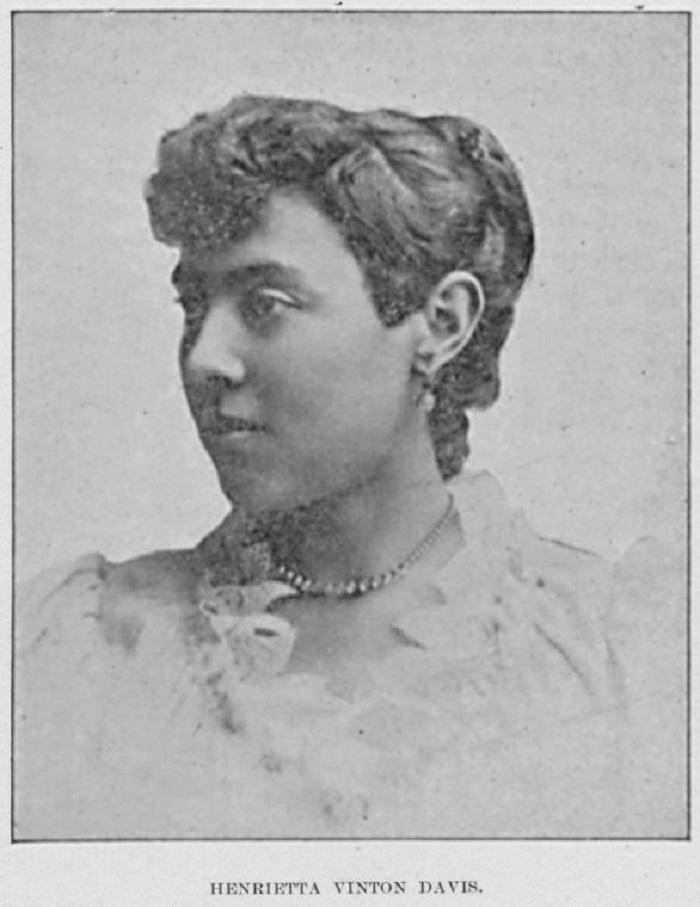

Davis was born in Baltimore and ultimately moved with her mother to Washington D.C. As a teenager, Henrietta worked as a public school teacher in Maryland. In 1881, Davis became the first African American woman to have a position in the Office of the Recorder of Deeds. Davis had theatrical aspirations and performed for integrated audiences throughout New England. She was one of the first African American women to perform the works of William Shakespeare.

Over the course of her life, Early worked to transform education for African Americans. Early is considered an early feminist as well as an abolitionist and suffragette. After working as a schoolteacher in the state of Ohio, she earned an L.B. degree from Oberlin College. This milestone made her one of the first African American women to earn a college degree. She went on to become a faculty member at Wilberforce University. Later, she moved to Xenia, Ohio where she worked as a principal for the African American schools. Upon moving to North Carolina, she began teaching at a school for girls through the Freedmen’s Bureau.

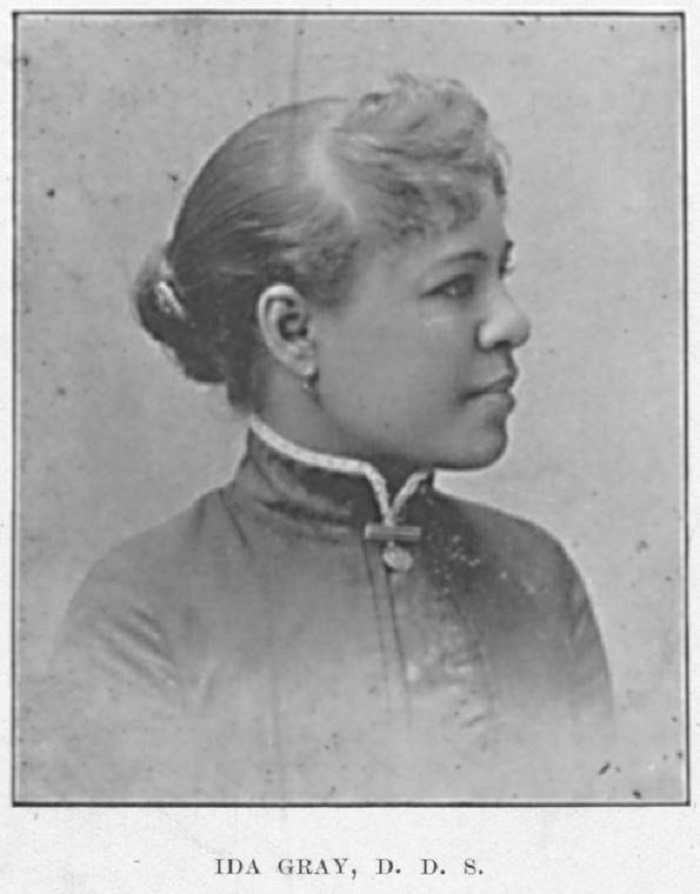

In 1867, Ida Gray Nelson Rollins moved with her aunt and cousins from Clarksville, Tennessee to Cincinnati, Ohio. Throughout high school, she worked in a dentistry office, which inspired her to become a dentist. In 1890, Gray became the first woman to graduate from college and become a dentist. She opened a practice in Cincinnati before moving with her first husband to Chicago, five years later. Ida became the first African American to open a dentistry practice in Chicago.