Who needs print anymore? Many people read the news on their phones, check out audiobooks from libraries, send emails and texts to their friends and loved ones, even post a virtual diary of their own lives on their social media accounts. Yet print has held on for dear life: From 2013 to 2016, the latest year for which figures are available, sales of print books have steadily increased at an average of 3.9%. Over 674 million books were sold in 2016 alone. With all those readers comes certain expectations of print. (Including, but not limited to, the ability to turn books around, which is not a new decorating trend.)

(Pictured: Not a new decorating trend.)

Books do not merely convey information, but also serve as objects themselves. They represent not only their outer binding and inner texts, but the act of reading itself. Who has not entered someone’s home and perused their bookcases, seeking some new insight of their host? But surrounding all books is an industry of writers, publishers, copyrighters, illustrators, booksellers and binders, all of whom participate in print culture.

Print culture officially began in the West with Johannes Gutenberg’s movable type press, but it was known in Korea as early as the 13th century. Before print, books in Europe existed mostly as manuscripts, handcopied by readers and scribes on parchment or vellum. Manuscript culture limited the spread of books and literacy to an elite few. But movable type, which was inexpensive, plus the introduction of paper led to both a thriving book publishing industry and increased literacy for the public. By 1600, it is believed that one out of every three men and possibly one out of every ten women in England could read.

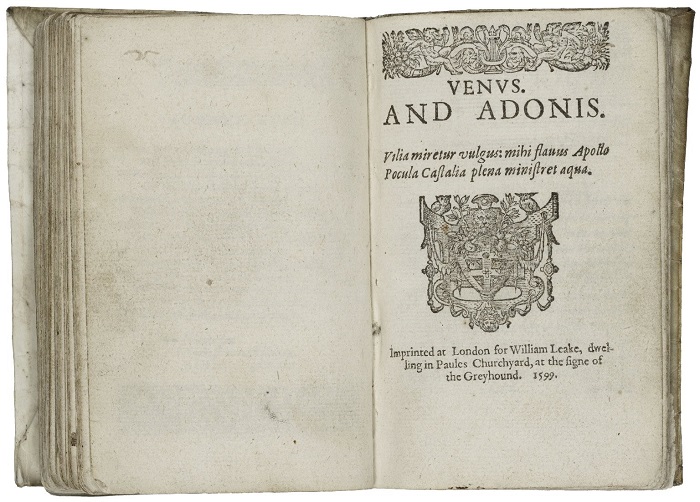

IU East now subscribes to a database that focuses solely on print culture. Our Adam Matthew database collection now boasts Literary Print Culture, a collection of primary documents from the Stationer’s Company Archive. The Stationer’s Company, founded in 1403 and recording every single printed book in England since 1559, established publishers’ rights to print specific books (and not print other publishers’ books). By keeping detailed records of every single printed book, thus proving authorship and publishing history for a number of works we know and love today, The Stationer’s Company essentially developed the idea of copyright for creative works. Their records have been used to prove the publication history of books like Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis (the most published of Shakespeare’s works in his lifetime) and the plays in his First Folio.

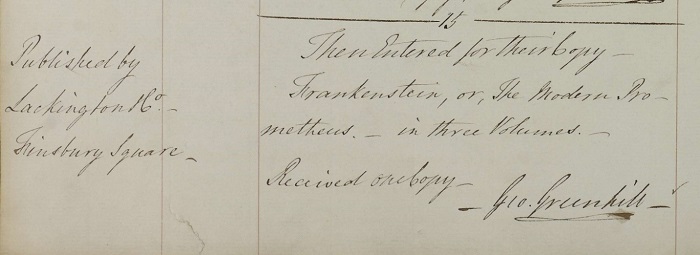

While Shakespeare is an incredible draw, however, most well-known British authors can be found here. For instance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was entered in January of 1818 – making this year the 200th anniversary of that book’s publication.

This database offers a wealth of tools and delights to capture the eye and heart of many scholars of print and lovers of literature. Need help using this database, or any of our other ones? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu.