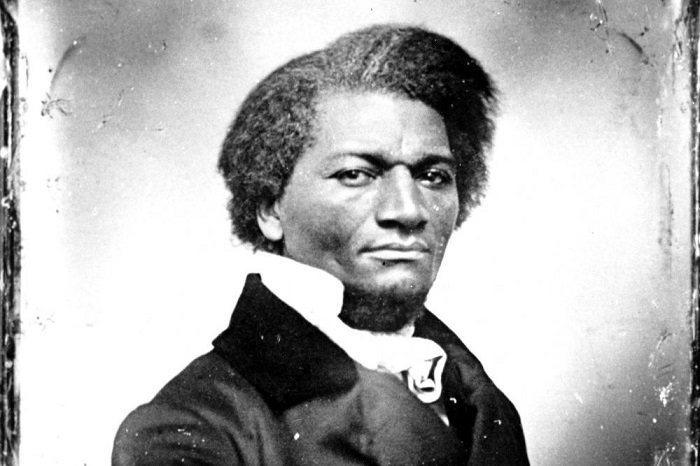

Born with the name Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in 1818, the man the world knows today as Frederick Douglass left an indelible mark on American history. From his bestselling first book, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, first published in 1845, to his groundbreaking work on both African-American equality and women’s rights to his career as minister to Haiti, Douglass is a figure whose time is immortal and whose words continue to carry deep and important meaning today.

Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland. He barely knew his mother, who was separated from him in early childhood and died when he was nine. The identity of his father, who was white, remained a complete mystery to him throughout his life. Yet from this uncertain background, Douglass developed an impeccable character, powerful literary skills and a forceful personality that made him the most famous African American in the Western world before he was 30 years old. He learned to read from the wife of his owner, Sophie Auld, but otherwise received no formal schooling and stole sheets of newspapers to improve his reading skills throughout his teens. Books were among his greatest treasures, and when he was 13 he purchased a copy of The Columbian Orator, a speech textbook that proved highly influential. He kept his copy of this book for the rest of his life, and it is now in the hands of the National Park Service. According to biographer David Blight, Douglass began speaking in front of fellow slaves by the time he was 15, and attempted to instruct them in reading through a secret school he led. Both his budding literacy and his public speaking activities at this age proved a precursor to his life’s work.

After an aborted attempt to run away in 1836, Douglass escaped slavery in 1838 at the age of 20. He borrowed papers and clothes from a free black sailor and used money he had earned as a caulker to book passage on a train from Baltimore to Delaware. From there he boarded a series of ships and trains to Philadelphia and New York, encountering little resistance but in constant fear of his identity becoming exposed. “I was a FREEMAN, and the voice of peace and joy thrilled my heart!” he wrote in his second autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855.

As a fugitive, however, his freedom was never a sure thing. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 allowed slaveowners to chase runaway slaves for their entire lives in any location of the US, and claim the children of female slaves as their property as well. Furthermore, descendants of slaveowners could also pursue and capture their families’ long-escaped slaves, as runaway Oney Judge’s case explains quite well. She had fled from George Washington’s household in 1796 but as late as 1846 she and her child could still be captured and returned to bondage. This meant that Douglass could also be returned to slavery and severely punished for his escape at any time. As a method of disguise, the former Frederick Bailey changed his name, initially to Frederick Johnson and then, after prompting by Massachusetts abolitionist and preacher Nathan Johnson, to the name he is best known by today.

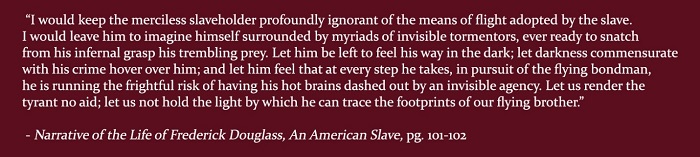

After he and his new wife Anna Murray moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, Douglass began his brilliant career. His speaking skills caught the attention of friends of William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator newspaper and an ardent abolitionist. Douglass then went on numerous tours across the US, where his powerful voice, sense of warm humor and harrowing account of life as a slave granted him tremendous popularity. In 1844, between tours, he began work on his first autobiography, a rich document that continues to reward and inform researchers and readers. Published in 1845, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, sold over 11,000 copies in the US in its first four months. The book also became a bestseller in the UK, where Douglass went on tour for three years to avoid being captured by his former owners.

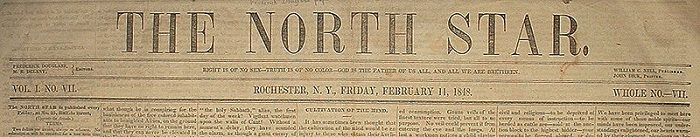

He continued to work for the cause of abolition, but also supported the rights of women. He was the chairman or co-chairman of a number of women’s conventions from 1848 through 1859 and actively spoke out on the cause of women’s equality and women’s suffrage. The masthead of his newspaper The North Star proudly stated “Right is of no sex – Truth is of no color – God is the father of us all, and all we are brethren,” a bold stance in the earliest days of the women’s rights movement, and continued to champion women’s suffrage alongside African American suffrage. It was only in 1868, when the 15th Amendment seemed on the brink of not passing, that Douglass began to emphasize black suffrage. Once it was ratified, however, as early as May 1870 he fully endorsed a 16th amendment which would have provided women’s suffrage. His dedication to the equal rights of women was forthright and prominent for much of his career. His last public act was his attendance at the meeting of the National Council of Women, only hours before his death on February 20, 1895.

After the Civil War, Douglass remained a sought after speaker, author and newspaper publisher, and worked in a number of government positions until his death. His final home in Washington, DC still stands as a national landmark, and his books continue to be published in expanded and annotated editions to this day. His papers are collected in a handful of archives, including the Library of Congress and IUPUI. Douglass’ work ensured the freedom of millions of people, yet his words still penetrate the consciousness of people everywhere. Interested in learning more about Douglass’ life and work? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu