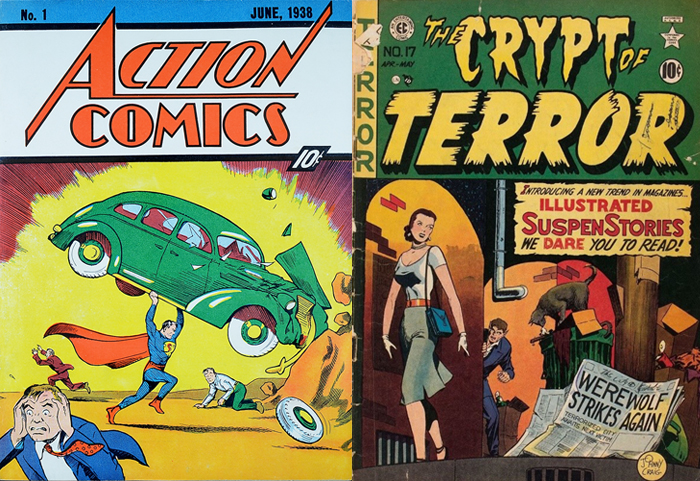

“It’s a bird! It’s a plane! No! It’s Superman!” While Superman is among the very first successful comic book characters, period, and the earliest comic book superhero, many important comics came in his wake. A market whose art and ideas were dominated by immigrants and their children, women and religious minorities, comic books were conceived by and for an audience left out of what might be termed “high culture.” The success of Superman, and other comic titles like New Fun, All-American Comics and others, led to a thriving comic market, where up to 15 million comic books were purchased by Americans every single week by 1941. Indiana University East boasts a large digital database of comic books, the Underground and Independent Comics collection, which includes work from EC Comics, one of the most beloved yet persecuted American comic publishers in history.

Two completely different takes on comics. Left: Action Comics #1 (the first appearance of Superman.) Right: The Crypt of Terror #17 (the forerunner to Tales from the Crypt)

The origins of EC Comics are full of firsts. Maxwell Charles “Max” Gaines (nee Ginzberg) created what is considered the first comic book, “Famous Funnies” in 1934. “Famous Funnies” was a collection of previously printed newspaper comic strips, presented in book form and sold originally at department stores. Its initial 250,000 copy run sold out, and Max knew he had something. He continued to develop and pitch ideas while hiring artists for his fledgling company, All-American Comics, which later picked up Superman on Max’s recommendation. He himself was not an artist, preferring to encourage talent to flourish. He sold his interests to the other partners of All-American Comics in 1946, retaining only one comic title, Picture Stories from the Bible, to be used to launch his own comic book publishing company. Max named it EC Comics, for “Educational Comics.”-

Famous Funnies #1, the issue that started the comic book industry

William Gaines, son of Max Gaines, inherited his father’s company in 1947 after Max died in a boating accident. Within a few years, William got rid of all the earlier titles, which had grown to include comics like “Saddle Justice” (westerns), “Animal Fables” (children’s stories) and “Land of the Lost” (adventure, based on the radio show of the same name.) In their place came the classic titles that EC, rebranded Entertaining Comics, has since become known for. They remain admired by collectors and comics connoisseurs to this day.

By 1948, comics were selling up to 80-100 million copies per month and bringing in annual revenues of $72 million for the industry as a whole. By 1950, EC was among the top publishers of comics, with new titles like Two-Fisted Tales (the brainchild of artist and editor Harvey Kurtzman and focused on war stories including the then-current Korean War), Weird Science (which sourced science fiction stories from Ray Bradbury) and the now iconic Tales from the Crypt (one of the most successful horror comics of all time.) Eleven titles in all were created, focusing on teenage and adult-themed content. They were also hugely successful – so successful that they caught the ire of psychologist Frederic Wertham.

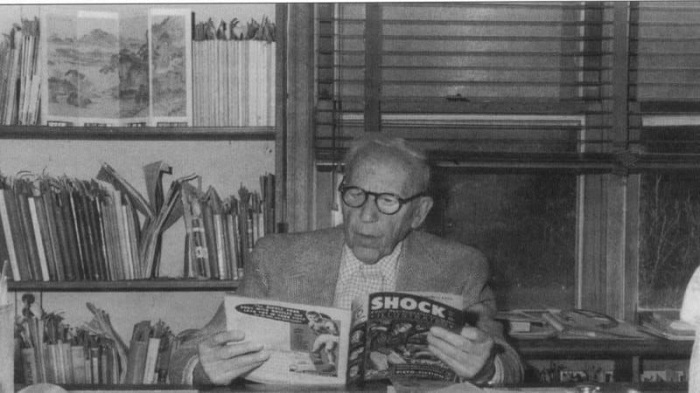

Frederic Wertham, reading one of those darned awful comics.

Conservative writers and critics had been unhappy with comics in the past. Children’s book author and columnist Sterling North wrote in 1940, “… the bulk of these lurid publications depend for their appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction – often with a child as the victim.” Other adjectives North used were “sadistic” and “graphic insanity.” He also charged “unimaginative teachers” with “forc(ing) stupid, dumb twaddle down eager young throats” and accused parents of committing child abuse for letting them read comics. But it was really Wertham who led the charge against comic books. As head of the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy and founder of the LaFargue Clinic in Harlem, Wertham believed that comics were morally dangerous, and chaired a symposium in 1948 entitled “The Psychopathology of Comic Books.” Wertham and some of his associates claimed a direct link between comics and violent behavior in young people, very similar to the purported link between violence and video games five decades later. Wertham continued to fight against comic books, including aiming for statewide bans on comics and writing articles in publications like Ladies Home Journal on the subject.

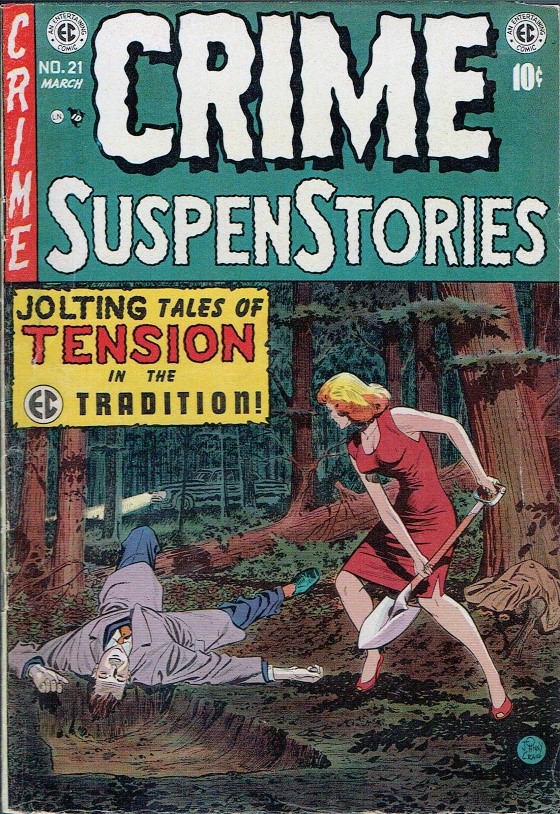

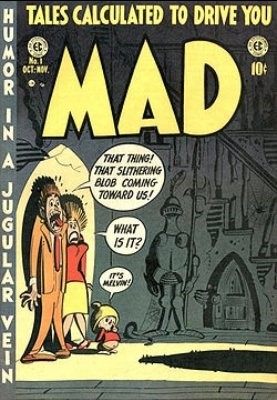

Meanwhile, comics continued to enjoy mass popularity, and EC Comics, while not the first seller of horror and crime comics, certainly contributed the most favored titles in the field. The EC Fan-Addict club was established in 1953, with bonuses like certificates, pins, badges and other rewards. Newer publications like Mad and its parody Panic had launched by 1953. EC Comics had also started publishing stories of significant societal importance. The story “Master Race” directly addresses Nazism and the Holocaust, while “Judgment Day” highlights racism between robots on another planet, with a black astronaut as a representative from Earth. The bread and butter of EC Comics, however, were lurid tales of murder, adultery, human dismemberment (like the famous “Foul Play” story in The Haunt of Fear, one of EC’s three horror-based titles) and other ghoulish activities. All of their horror, crime and science fiction titles, along with competing titles from other publishers like Timely Comics (edited by Stan Lee), launched a nationwide trend away from superhero comics. 30 million copies of horror and crime titles were printed each month, with estimated gross earnings of $18 million.

One of the many top-selling comics by EC at the height of its fame

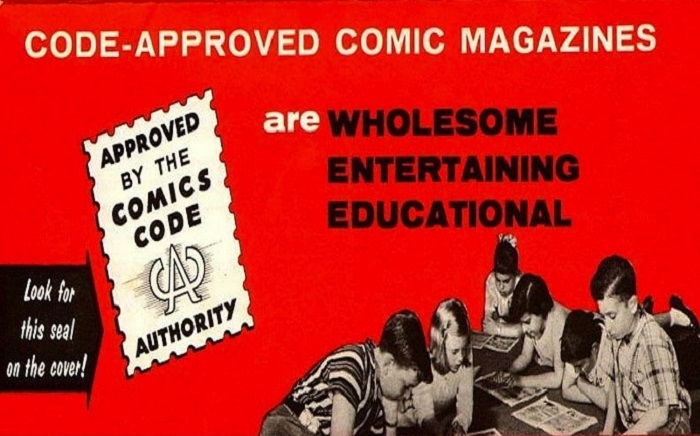

However, Wertham wasn’t done. Wertham’s work, including his book Seduction of the Innocent, spurred two US Senators, Estes Kefauver of Tennessee and Robert C. Hendrickson from New Jersey, to launch a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. Wertham testified against the comic industry, citing his own flawed studies done at the LaFargue Clinic. Of all the figures in the comic book industry, the only one to testify was Gaines. Only a few newspaper comic strip artists testified, including Walt Kelly and Milton Caniff, mostly against comic books. Despite critique regarding Wertham’s findings and methods, the Subcommittee recommended self-policing measures for the comic book industry, a move that led to the Comics Code Authority in 1955.

Along with new state laws banning most comics and distributors terrified of breaking these laws, the regulations by the Comics Code Authority crushed EC Comics almost entirely out of existence. With these rules came heavy restrictions, such as leaving words like “horror” and “terror” out of the titles of comics to censure over content. While Gaines and EC attempted to work within these regulations, releasing new titles like Impact and MD, none of these titles were profitable or , to the public, interesting. Some EC Comics artists, like Jack Kamen and “Ghastly” Graham Ingels, never worked in the comic trade again. In order to keep the doors open at EC, Gaines took Mad, by that point the only successful publication for EC, and dubbed it a “magazine”, which put it outside the purview of the Comics Code Authority. Gaines sold Mad Magazine to the Kinney Company in the early 1960s, but remained active with the publication until his death in 1992.

Mad started off as a comic in 1952, but became a magazine in 1956.

While EC Comics is no more, their influence continues. A highly successful HBO television series, Tales from the Crypt, based on stories from all of the old EC Comics titles, ran for 93 episodes from 1989 to 1996. It was produced and directed by the likes of Robert Zemeckis, and featured actors like Christopher Reeve and Arnold Schwarzenegger and music by artists like Warren Zevon. Spinoffs included a Saturday morning cartoon, a handful of movies and even a Christmas album. Unfortunately, a proposed new series for TNT has been “buried” for the time being. But don’t let that “kill off” your curiosity! Interested in horror comics? Want to know more about comics and society? Or are you interested in comic book history in general? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu