“The whole modern method of historical research is founded upon the distinction between original and derivative authorities. By original authorities we mean either statements by eye-witnesses, or documents, and other material remains, which are contemporary with the events which they attest. By derivative authorities we mean historians or chroniclers who relate and discuss events which they have not witnessed but which they have heard of or inferred directly or indirectly from original authorities.”

– Arnaldo Momigliano, Studies in Historiography, 1966

When conducting research, you will often need to find and use specific types of resources. That could include peer-reviewed work, or to use a book or a video as a reference. One common and very important type of source students are often asked to find is a ‘primary source’. Depending on what your class is, ‘primary source’ can mean different things. Generally, though, it means that the writer or speaker was an original party to or direct witness of the things described.

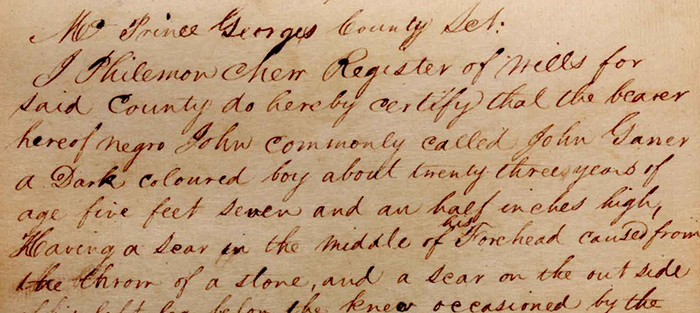

Primary sources are often consulted for history classes. A primary source in the historical sense often takes the form of a letter, journal, memoir, oral history, or interview. Historical research is founded on consulting these – mere reliance on another historian’s interpretations, without examining the underlying evidence yourself, is a recipe for professional failure, censure, and even ridicule. While the consequences are not quite so dire for a student, it is important to learn how to use these types of works in your classes to truly understand the field.

Fortunately, there are a lot of databases designed to help you do this. Try ones like African-American History Online, American Civil War: Letters and Diaries, American Indian History Online, American Women’s History Online, British and Irish Women’s Letters and Diaries, Gale Primary Sources, Modern World History Online, Oral History Online, North American Immigrant Letters & Diaries, The Sixties: Primary Documents and Personal Narratives, and Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. Even a database that seems by nature to be a derivative source, the Britannica, includes an option to search specifically for primary documents.

On campus, our Archives also holds a number of oral histories. This collection is particularly strong in documenting the 1968 Richmond explosion and the Starr-Gennett companies, as well as a number of interviews taken with students, faculty, staff, and administrators about IU East’s own history, to be included in the IU Bicentennial Oral History project. Speaking of interviews, the video database AVON also includes thousands of usable sources, included amongst secondary documentaries and television programs, which can add a multimedia component to your project.

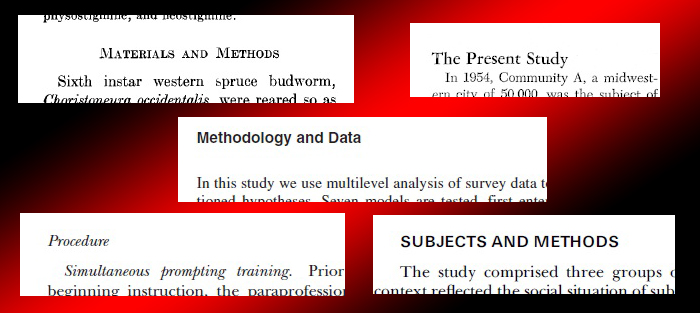

In science or social science classes, ‘primary sources’ are those that include scientific experiments in which the authors participated – in other words, that the writers conducted their own research, creating new data in the process. An article like this may still review the work of other scholars, but most of the article will be focused on the writers’ own experiment. Primary source science articles can easily be identified if they include sections with labels like ‘methodology’, ‘procedure’, ‘the present study’, or something similar, which describe exactly what the authors did. These are much easier to find than historical primary sources, because they are included in the normal science databases instead of being largely segregated into specialized ones.

Archaeologically, an ancient document is sometimes also referred to as a primary source if there is simply no known antecedent for its content, regardless of whether there is agreement among historians that the author had firsthand knowledge of the subject. So, for example, the Roman emperor Tiberius, who ruled from 14-37, was biographized by Velleius Paterculus in his first century Compendium of Roman History. While parts about earlier Roman history are influenced by other historians like Quintus Hortensius and Cato, the part about Tiberius has no known literary influence and is considered ‘primary’ in this ancient sense. Later historians, like Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, all integrated Paterculus’s work and are thus considered secondary sources. Similarly, in the Bible, the Gospel of Mark is considered a primary source by most scholars because none of its content comes from any identifiable underlying source while the Gospel of Luke is a secondary source because it draws substantially from the Gospel of Mark, restating about fifty percent of its material. This use of ‘primary source’ isn’t likely to come up in many of your classes, but is important to archaeologists, ethnographers, and ancient historians.

Regardless of what field you are researching, if you need primary sources, the IU East library offers a wealth of it. Do you need any help locating a primary source for your classwork? You can ask us at iueref@iue.edu!