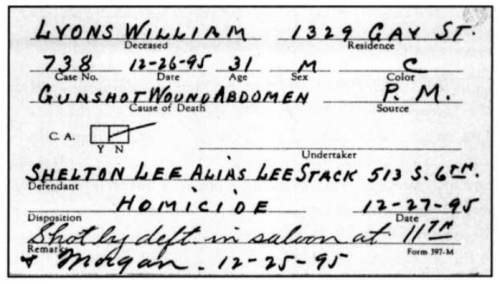

On the evening of December 25, 1895, “Stag” Lee Shelton was doing the 19th century version of a bar crawl when he entered the Bill Curtis Saloon in St. Louis. He took a seat next to William Lyons, and they talked about a number of different things. But when the subject switched to politics, Lyons and Shelton, who whipped up support for opposing parties, began hitting each other’s hats as a form of retaliation. Shelton ultimately broke the crown of Lyons’ derby hat. Lyons asked for five bits (about $1.25) to replace it. When Shelton refused, Lyons took Shelton’s Stetson hat. Shelton promptly shot Lyons, took his hat back and walked out of the bar. Lyons died of his injuries only hours later. After two trials, Shelton served 14 years of a life sentence before being paroled in 1909. In 1911 then reentered prison for battery and petty theft. He died a year later from tuberculosis. These are the basic facts, well documented and enduring. However, at the same time of the murder, one of the strongest American mythologies was born: the myth of Stagolee.

Stagolee is classified as a murder ballad in folklore circles. The earliest version of Stagolee may have come out shortly after Lyons’ shooting. It began as a work song in the African American community, and according to historian Cecil Brown may have been transmitted along shipping lines through black workers. As early as 1911, it was already famous (or archetypical) enough to be included in a list of “hero songs” that were common in black communities. That same year, two versions were published by folklorist Howard Odum. Indeed, even though Shelton committed first degree murder, the Stagolee songs (there are hundreds of versions) transforms Shelton from a “bad man” to a heroic figure.

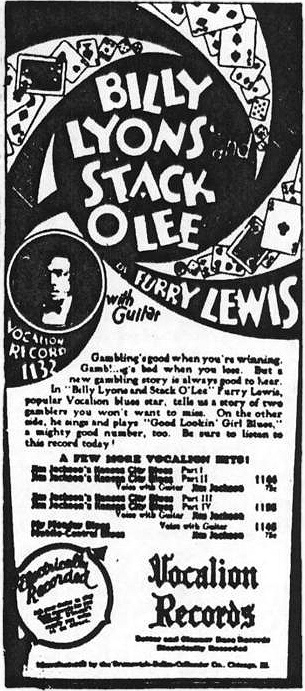

It is worth hearing those songs. John Lomax (1867-1948) was the first folklorist to develop an interest in the Stagolee songs, and he collected transcriptions of them as early as 1910. However, the first version with lyrics was performed by blues singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey in 1926. Released as a single on Paramount, a small independent label associated with the Wisconsin Chair Company, it was one of a successful string of singles for her. Other versions quickly followed: Frank Hutchinson in 1927, Long Cleve Reed and Harvey Hull (also known as the Down Home Boys) in 1927, Furry Lewis in 1928, Cab Calloway in 1931 (whose version is more of a parody than a direct cover), Woody Guthrie in 1931. Of the earliest versions, the one by Mississippi John Hurt in 1929 is considered the most influential, and it bears a clarity other versions of this time period do not. Of these early versions, the careful listener will also notice that the story changes – for instance, in both the Hurt and Guthrie versions, it’s Lee who begs for his life. In Hull’s version we see the first recorded instance of gambling as part of the Stagolee story, even though there was no gambling in the real life turn of events. Sometimes Billy Lyons has three children and a wife; in others, he only has two (a boy and a girl.) In real life, Lyons had three children but was unmarried. In all versions, fact and fiction intermingle to create a new character – that of Stagolee – who represents a variety of human emotions and conditions usually unique to the African American community.

While popular music now boasted a variety of recordings, John Lomax, accompanied by his son Alan, continued to seek out folk renditions of Stagolee. In 1948, two especially interesting versions were recorded; they are now part of the Library of Congress. The first was recorded by Bama, the stage name of WD Stewart. By the time of this recording, the Lomaxes had long sought out folk songs in places such as brothels, churches and fields. This particular recording was taken down when Bama was a prisoner, and is performed as a prison work song. The breaks in the verses are intended to serve as cues for workers to perform an action in unison – chopping into a tree, for instance, or hoeing. What makes it so interesting, besides its obvious quality, is how it hearkens back to the earliest origins of Stagolee as a song. A second version, performed by Vera Ward Hall, adds a soft mournful melody not found in any other version, plus includes a significant number of details scattered across other versions. In a way, it serves as a compendium to the Stagolee myth’s variants.

When the rock and roll era emerged around 1950, Stagolee came along and became even more popular than ever. In 1950, New Orleans piano player Archibald released a version on Imperial Records, produced by the legendary Dave Bartholomew. It hit #10 that year on the newly rechristened Rhythm and Blues Billboard chart. Archibald’s version is the first of what becomes a very long string of covers, many of which use the same lyrics, similar melodies or both.

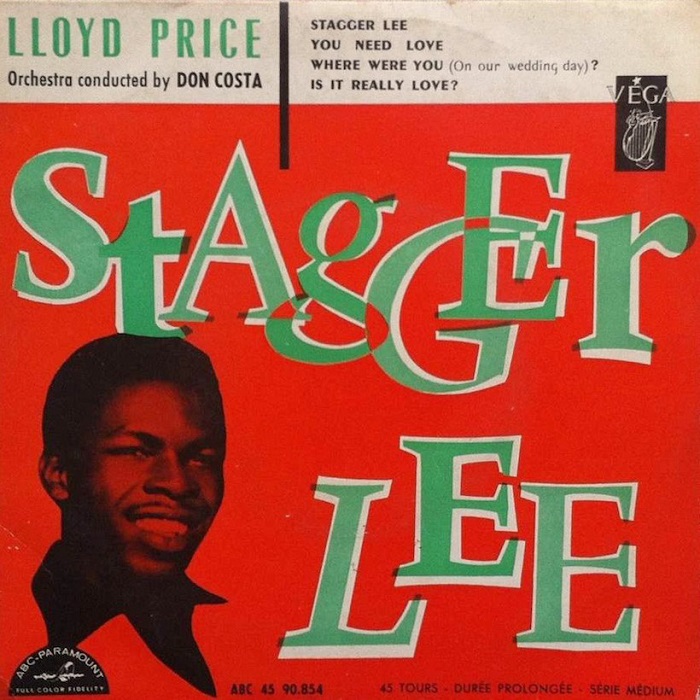

But this development is not because of the popularity of Archibald’s version. Instead, the credit goes to Lloyd Price for his 1958 cover of Archibald’s version. Price, another New Orleans native and a one-time labelmate of Archibald, released Stagger Lee on ABC-Paramount Records in December of that year, hitting #1 for four weeks, one of the most successful records of the year. Other cover versions abounded: The Isley Brothers in 1963, The Righteous Brothers in 1966, James Brown in 1967, Wilson Pickett in 1967 and Neil Diamond in 1979 and just a few among the dozens recorded since Price’s hit.

124 years after the events which triggered Stagolee, the song continues to be performed. Although no one can agree about the spelling of the song’s name – Stagolee, Stackalee, Stack-O-Lee, Skeeg-a-lee, Stackerlee and Stagger Lee are some of the variants – and despite the heavy fictionalization of Shelton’s murder of Lyons, the song remains a source of musical inspiration. Of the more recent versions, some of the better known have been recorded by Beck, the Grateful Dead and actor Hugh Laurie. There is little doubt that musicians will continue to perform this song, under any of its names, for the foreseeable future.

Want to learn more about American folklore? Interested in rock and roll history? Curious about other great American folk songs that became rock and roll standards? Ask Us! iueref@iue.edu.