On August 26, 1920, women in the U.S. secured the right to vote. It was a victory 80 years in the making, opening voting rights on a national level to all women for the first time. While the Constitution first extended voting privileges, it did so only for property-owning men. Eventually, all men were allowed to vote, via a patchwork of state laws and the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted black men the right to vote. But women were continuously denied the same privileges, under charges such as “wom(e)n would run into excesses” or that they would abandon their “proper place” as homemakers, wives and mothers.

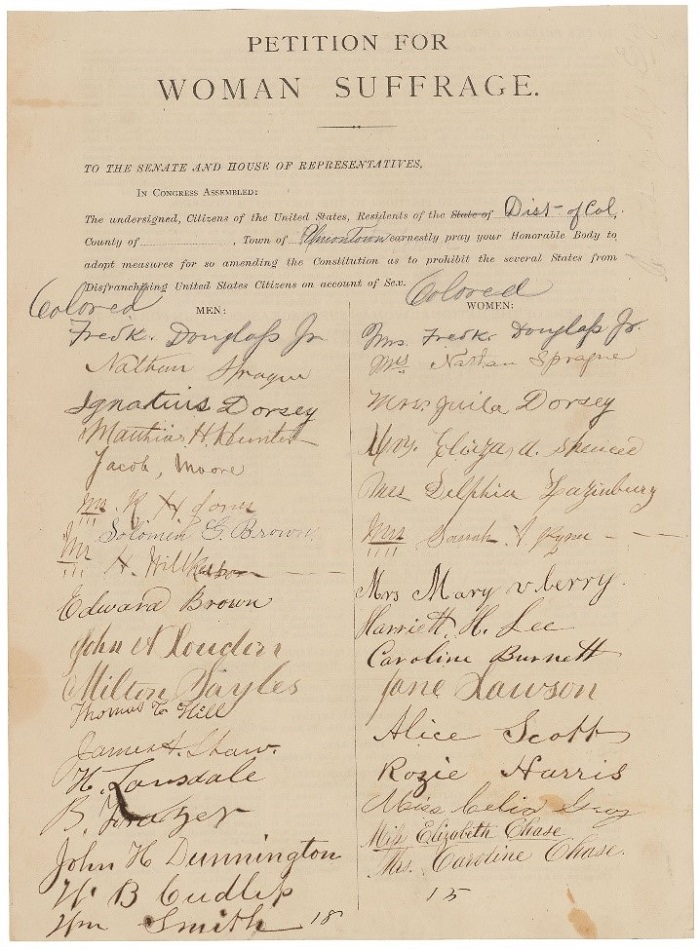

The fight for suffrage began in 1840, when abolitionists Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, serving as delegates from the United States, were denied entry to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840. William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society, encouraged women to participate in the abolitionist movement, and Mott was one of those who established the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. Stanton, who was well educated and married an abolitionist, was attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention as part of her honeymoon. Mott and Stanton shifted their attentions to include women’s rights, and they brought together the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, the first of its kind, on July 19th and 20th, 1848. At the convention, a Declaration of Sentiments was issued, which served as a guide of sorts for the rights that women were denied. Other speakers included Frederick Douglass, the only Black attendee, who spoke in favor of women’s suffrage and continued to support women’s rights throughout his life. Fourteen days later, the Rochester (NY) Women’s Rights Conference was held, cementing the successes of the Seneca Falls conference. Speakers included Mott, Stanton and Douglass; abolitionist William Cooper Nell and the parents of Susan B. Anthony, Daniel and Lucy Anthony. Susan would soon become an in-demand speaker in her own right, eventually getting arrested for trying to vote.

After these initial events, the women’s rights movement grew in both power and prominence, remaining closely aligned with the abolitionists. The first National Women’s Rights Convention brought together older speakers such as Douglass and Garrison, and introduced new faces such as Lucy Stone, Sojourner Truth and Ernestine Rose. Stone, the first woman to earn a college degree in the state of Massachusetts, had already been lecturing on the abolitionist circuit when she organized the 1850 conference. Truth, a former slave, walked to freedom in 1826 and won the freedom of her son Peter in court in 1828. Rose, a Polish immigrant who spoke multiple languages and had already established herself as a speaker in New York, was also elected to the conference’s executive committee. All three of them would have long and fruitful careers as speakers and advocates for the rights of women and Blacks, and in Rose’s case, freethinkers as well.

The women’s rights movement, always infused with the abolitionist movement, temporarily stalled during the Civil War but renewed with the passage of the Fourteenth amendment granting the right to vote to Black males. Mott, Stanton, Anthony, Douglass and Stone continued to advocate for women’s rights, particularly the right to vote. As a result of the Fourteenth amendment, however, a schism split the movement in two. Stanton and Anthony founded the National Women’s Suffrage Association (pressing for a Constitutional amendment for voting rights) and Stone leading the American Women’s Suffrage Association (working with states to extend voting rights to women; by 1890 women could vote in Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, Idaho and Washington.) The two groups combined forces in 1890, renamed themselves the National American Women Suffrage Association, and continued to lobby for voting rights.

Not everyone was interested in extending rights to women, including some women. Susan fenimore Cooper, daughter of author James Fenimore Cooper, argued in 1870 that women, being of weaker mind and stronger morality, should extend their influences no wider than the home. The idea of men’s and women’s spheres and differing abilities remained a popular idea. “This difference in the sexes is the first and fundamental fact in the family; it is therefore the first and fundamental fact of society,” wrote Lyman Abbott for the Atlantic in 1903. Others argued that women did not actually want the vote. A 1915 pamphlet urging men to vote against suffrage claimed granting women the right to vote was “undemocratic” and “a means to an end – the end being a complete social revolution.”

During this period, the first woman ever to earn a seat in Congress was elected. In 1916, Montana suffragist Jeannette Rankin, a pacifist and later anti-war activist, was elected to the House of Representatives. Women had gained the right to vote in Montana in 1914, largely due to Rankin’s efforts, and as a representative she was a founding member of the Committee on Woman Suffrage. As Rankin put it “I want to be remembered as the only woman who voted to give women the right to vote.” While her attempts to introduce a women’s voting rights amendment were not successful, her work led to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which was ratified less than two years after she left office.

While the right to vote has been enshrined in the Constitution for 100 years, that right, in order to have any meaning, must be renewed regularly. Voting remains the best way to honor the memory of our foremothers. Check your voter status, or register to vote in your state.

Do you have any questions about the history of voting? Want to know more about how voting impacts your community? Curious about misinformation related to voting? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu