While Americans have always performed music, serious study of American musical forms only begins in the 20th century. John Lomax, beginning as a graduate student at Harvard, was among the very first to take interest in traditional American music, and he began his work with “cowboy” songs, which detailed the lives of what he felt were “authentic” Americans and their experiences. Although his viewpoint could comfortably be considered naïve today, his work, along with that of anthropologist Franz Boaz and, slightly later, poet Carl Sandburg, became the foundation for American folk music studies.

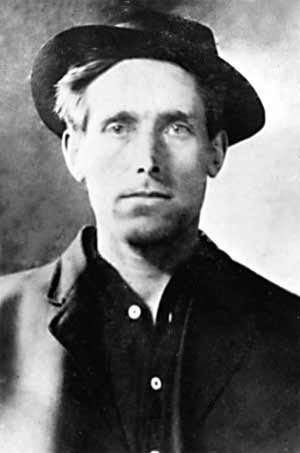

It is from folk music that the protest music movement stems. The very first protest singer/songwriter was a Swedish immigrant, born Joel Hagglund in 1879. After his parents died, he accompanied his brother on a ship bound for the US to find work. Somewhere on that journey he changed his name to the more Americanized Joe Hill, the name we know him by today. However, instead of a land of opportunity he found workers who were being oppressed from all sides. Hill became a union activist, traveling across the country to urge miners, longshoremen, railroad workers, steel workers and others to organize and strike for fair wages and better working conditions. In order to spur workers into action and give them courage, he began writing songs in favor of union causes. Because most laborers at the time were illiterate and many spoke languages other than English, music became a unifying force for all of them. In 1914, Hill wrote. “A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over; and I maintain that if a person can put out a few cold, common sense facts into a song and dress them (the facts) up in a cloak of humor to take the dryness off them, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial in economic science.” Hill’s songs included “The Preacher and the Slave,” which identified religious hypocrisy; “Casey Jones,” which exposed the anti-union tendencies of the now-legendary engineer; and “The Rebel Girl” which highlighted women in the union. He was killed by a firing squad in 1915 after a trial on what were likely false murder charges. His work has been performed by hundreds of artists, including a tribute from Salt Lake City where Hill died, and a folk song detailing his life was written by renowned protest singer/songwriter Phil Ochs in 1968.

Hill’s work sparked a movement for more issue-driven music, although much of the earliest work was not collected due to competing definitions of what qualified as folk music among scholars. What ultimately boosted interest in folk, and by extension protest music, was the nascent recording industry’s interest in regional and non-commercial music forms. Blues, bluegrass and early country and jazz songs were initially viewed as unsophisticated and unpopular by major labels such as Columbia and Victor, which focused on pop, classical and dance music. It was left to smaller labels like Gennett, Black Patti and others to capture these musical forms, but even here folk music tended to slip through. By the time of the Great Depression, however, the majors focused more of their energy on these non-mainstream musical forms, and one of the first ever mainstream protest songs released on a major label was performed by Aunt Molly Jackson, a union organizer in Kentucky. Her song “Ragged Hungry Blues” was released on Columbia Records in 1932, and while it was her only professionally released recording, many of her songs have been preserved by the Library of Congress. Jackson was in New York City at the time of the recording to meet with musicologist Charles Seeger, who was working with the Composers Collective, a group of musicians and songwriters who were busy composing music for workers and members of the political left. Seeger, like most of his Collective confreres, possessed classical training and wrote in a classical form. Jackson, a self-taught musician firmly in the folk tradition, sang her protest songs at a meeting of the Collective, and Seeger realized his “elevating” approach would not be effective for the common worker.

But it was his son, Pete Seeger, who would become famous for popularizing folk and protest music. The third son of Charles, Pete was a Harvard dropout who took up the five-strong banjo in his teens. Pete’s first commercial performance was the “Grapes of Wrath” concert at Forrest Theater on March 3, 1940, one of the most important events in folk music history. On stage that night, in addition to Seeger, were Jackson, Lead Belly, Josh White, British folksinger Richard Dyer-Bennett and an Oklahoman who had traveled by train from California, Woody Guthrie. This event brought together Guthrie and Seeger for the first time, and they became close friends, espousing a mentor-student relationship.

Guthrie is perhaps the most important figure in American folk music. Born in Okemah, Oklahoma to a merchant father and homemaker mother, Guthrie initially appeared to be more inclined toward visual arts. It was not until his late teens where he showed much interest in music, when he lived with his uncle after the institutionalization of his mother due to the degenerative disease Huntington’s Chorea. Guthrie began writing music in his late 20s, after learning songs from hoboes, farmers and others. He migrated to California to escape Dust Bowl poverty in 1937 and with his cousin Jack started a Los Angeles radio show, “the Oklahoma and Woody Show”. When Jack left, Woody teamed with “Lefty Lou” Maxine Crissman and ran the show until late 1939. He had been in New York all of three weeks when the Grapes of Wrath concert was held, and it was after his move to New York that Guthrie wrote his most enduring songs. “This Land is Your Land,” an American classic, was initially composed in 1940 as a riposte to Kate Smith’s “God Bless America.” It was quickly forgotten, and remained unrecorded until Guthrie returned to New York on leave from the Merchant Marine in 1944. The song became influential in the 1960s, when Peter, Paul and Mary were the first to cover it on a top-selling commercial release in 1962. Other artists who have covered it since include Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Sharon Jones, My Morning Jacket and the Avett Brothers, and this list is not exhaustive by any means. Other influential Guthrie compositions include “Pastures of Plenty”, “Pretty Boy Floyd”, “Deportee” and “So Long, It’s Been Good Tuh Know Yuh.” He and his legacy of social justice, antifascism and equality have influenced every generation of musicians ever since. Unfortunately, his highly prolific career was cut short when he was institutionalized in 1952 with the same disease that took his mother’s life so many years earlier. Guthrie died in 1967 at the age of 55.

After World War II, the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was charged with removing Communist influences from American society, tore through the folk community on the perceived basis that many were previously members of the Community Party or espoused communist viewpoints. While this claim was mostly false and based on little more than circumstantial evidence, the careers of numerous folk artists, including Pete Seeger, Paul Robeson and Oscar Brand, were adversely affected. All three performed outside of the United States for most of the 1950s, continuing to support causes such as equal housing, fair labor standards and, increasingly, civil rights. Folk music remained popular in America, however, with the advent of folk music groups such as the Weavers, founded by Seeger in 1949, and later such artists as Harry Belafonte and the Kingston Trio.

It is the early 1960’s, however, that most people alive today associate with American folk and protest music. Greenwich Village began as a working class Italian neighborhood, but by the late 1950s a musical community had built up around Washington Square Park. Although this caused tensions with local residents, more musicians streamed in and new folk music venues such as Gerde’s Folk City, the Gaslight and Café Wha? opened in response. Among these young folksingers, who were often influenced by Elvis Presley as much as Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, were Tom Paxton, Buffy Saint-Marie, Eric Andersen, Phil Ochs and, most famously, Bob Dylan.

Although his career spans seven decades, Dylan’s protest music era is short but deeply important. Born in 1941 to a middle class Jewish family in Hibbing, Minnesota, he moved to Greenwich Village in 1960 after dropping out of college. Initially patterning himself exclusively on Guthrie and Odetta, he began writing his own compositions shortly after his arrival in New York. Among his first songs was “Song to Woody,” a reverent poem about Guthrie, who was by then virtually unable to speak, set to a basic melody. Dylan’s star rose meteorically, with a recording contract with Columbia Records signed in late 1961, a management contract with Albert Grossman (who helped plan the Newport Folk Festival for most of its early years) and, in his personal life, a partner in fellow singer Joan Baez, who had already become a star due to her ethereal voice. Baez would take Dylan on tour with her, introducing him as a surprise guest and duetting with him on his own original compositions. While Baez focused almost entirely on traditional ballad material, Dylan was touted as a songwriter, and his compositions, which included “Blowing in the Wind”, “Masters of War”, “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall,” “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “The Times They Are a-Changing”, were covered by numerous folk, rock and rhythm and blues artists. They also crossed over to popular audiences, and many of them have since embedded themselves into popular culture. Yet he only performed protest music for a handful of years – by the time he migrated to rock music full time in 1965, he had almost completely abandoned both folk and protest music.

Although Dylan’s “Masters of War” was among the first songs to address Vietnam, it was not the first. Instead, the first Vietnam War protest song was likely written by Phil Ochs, who served as both rival and foil to Dylan at times. Born in 1940, Ochs initially considered a career in journalism before dedicating himself to songwriting. He moved to Greenwich Village in February 1962, already with a handful of songs in tow, and by September of that year was developing a reputation as a “singing journalist” who took his material from newspapers of the day. Almost all of his works up to his last few records, including unpublished and unreleased material, concerns social topics as far ranging as medical costs, US-Cuban relations, the negative outcomes of colonialization and civil rights in the southern United States. But his overarching theme was war, and as someone who was eligible for the draft, he protested the Vietnam War early and often. “Vietnam” was first published in October 1962 in issue #14 of Broadside Magazine, one of the major publications for protest oriented folksingers of the period. Although he didn’t record the song until 1964, and then in a longer, talking blues form, he was the first songwriter to address the war, and continued to protest for almost the rest of his life against it. His other antiwar songs include “The War is Over” (which directly inspired his friend John Lennon’s “War is over if you want it” campaign in 1972), “White Boots Marching in a Yellow Land”, “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” and “Draft Dodger Rag.” As a result of chronic depression, bipolar disorder and alcoholism, he died by his own hand in 1976, but not without leaving one of the most potent bodies of work in American folk music.

Protest music did not die with the 1960s or with the Vietnam War. However, from the late 1960s onward, it took on new topics and new musical forms. James Brown wrote and performed one of the most important songs in the Black Pride movement with his single “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)”, which kicked off a renaissance of black protest music that began in 1939 with Billie Holiday’s version of “Strange Fruit.” Although protest music up to this point has been associated primarily with white and Jewish musicians, it is important to note that there have always black protest songs and black protest singers, not all of whom are immediately obvious. While Nina Simone is readily associated with protest music, artists such as Sam Cooke recorded protest-oriented music, such as “A Change is Gonna Come,” which was released around time of Cooke’s death in 1964. With this greater shift to black performers came an influx of new musical forms, including soul (Sly and the Family Stone, “Everyday People” and “Stand!”), gospel-influenced pop (The Staple Singers’ “Respect Yourself”), funk (“Fight the Power” by the Isley Brothers) and Motown (“Pastime Paradise” by Stevie Wonder and “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye.) Other artists like Tracy Chapman work in folk music, but address concerns like poverty and social inequality.

Moving into the 21st century, protest music has become even more diverse and more willing to directly confront current events. In 2004 Faithless, a British Buddhist electronic group, protested against the US invasion of Afghanistan with their single “Mass Destruction.” In 2018, blues artist Keb’ Mo’ teamed up with country legend Rosanne Cash to release a song about the lack of female leadership in political office. In the same year, Childish Gambino released the powerful “This is America”, which offers a definition of what it means to be black in America. And the current crop of protest music fighting against police brutality and black inequality has taken tremendous power and popularity. Usher, Anderson.Paak, J. Cole and H.E.R. all released protest songs in the wake of Black Lives Matter, drawing even more attention to social justice issues. Of all these listed, it is only a small fraction of the protest songs released in the last two decades.

American protest music, now over 100 years old, remains among the most vital, proactive and participatory forms of music produced, spurring to action people from all positions in life to improve their world and the lives of others. Although some have argued that protest music is, by nature, ephemeral and temporary in terms of interest and power, its long history proves otherwise. Are you interested in discovering more protest music throughout American history? Are you curious about the historical, social or political issues that urge people to write and perform protest music? Would you like to discover specific era of protest music for yourself? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu or click this button: