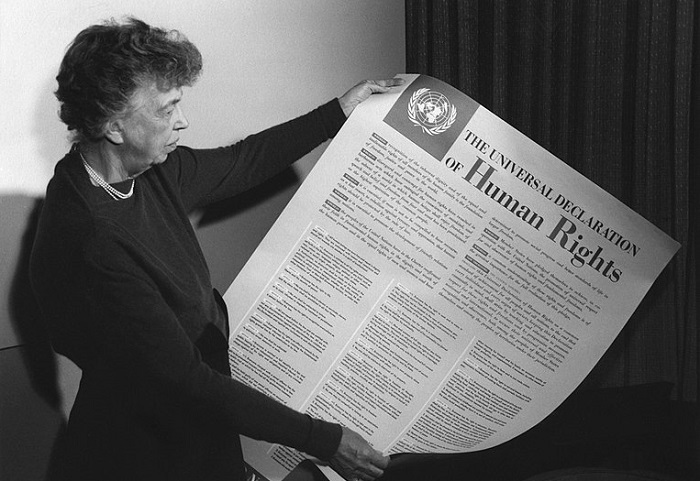

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was signed by United Nations members on December 10, 1948 (a day that is now celebrated as Human Rights Day). Eleanor Roosevelt, the chairwoman of the UN committee that drafted the document, referred to it as humanity’s Magna Carta. In the wake of the atrocities committed in World War II, there was a strong need to formally define rights in a manner that all nations would understand them in the same way. The document was based around four core freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from fear, and freedom from want. In 30 articles, the UDHR spells out individual rights and freedoms to dignity, liberty, and equality, including listing recommended remedies and penalties for their violation. Like America’s Declaration of Independence, it is not binding law but rather a kind of values statement, the spirit of which informs and undergirds many other international treaties and laws, and all 193 member states of the United Nations have ratified at least one of these. The full text of the UDHR can be read here.

The library offers access to many resources useful for the study of the UDHR or human rights more broadly, from a diversity of perspectives. American History Online offers primary and secondary sources about the Declaration itself and the international human rights movement. Databases like CQ Researcher have articles on numerous human rights issues, and Archives Unbound contains subsets dedicated to international developments and problems. The Digital National Security Archive is also international in scope, but focuses on America’s involvement in each issue. Civil Rights and Social Justice is focused entirely on the United States, and includes law, court cases, historical articles, and civil rights publications. Contemporary Women’s Issues looks at international rights issues as they impact women, in particular.

There are also books about the UDHR itself, like the ongoing Universal Declaration of Human Rights Series (four of a planned twenty volumes are available so far), such as Securing Dignity and Freedom Through Human Rights (Article 22) by Janelle Diller or Cultural Rights in International Law (Article 27) by Elissavet Stamatopoulou-Robbins; The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Origins, Drafting, and Intent or The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Holocaust: An Endangered Connection, both by Johannes Morsink; and Philosophical Theory and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by William Sweet.

There are many other books about human rights more generally, such as Human Rights and Social Justice in a Global Perspective: An Introduction to International Social Work by Susan C. Mapp, A Most Uncertain Crusade: The United States, the United Nations, and Human Rights, 1941–1953 by Rowland Brucken, Vulnerability and Human Rights by Bryan S. Turner, Grounding Human Rights in a Pluralist World by Grace Y. Kao, The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History by Samuel Moyn, Power and Principle: Human Rights Programming in International Organizations by Joel E. Oestreich, The Human Rights Paradox: Universality and Its Discontents by Steve J. Stern, Wronging Rights? Philosophical Challenges for Human Rights by Aakash Singh Rathore, or Cultural Heritage in Transit: Intangible Rights As Human Rights by Deborah Kapchan.

Seeking more information about human rights? Ask us! iueref@iue.edu or click here: